a few words about...

Small lamps manufactured and marketed for medicinal purposes are commonly found in antique shops and on the Internet. The most common variety found is the Vapo-Cresolene "lamp." These items are not technically lamps, but rather employ a small lamp or flame as a heat source. It is possible to find complete examples, but these lamps are often missing some of the parts, such as the tin dish or Olmstead-type milk glass chimneys. Occasionally these lamps are found in their original box, complete with instructional sheets, testimonials and an extra wick included. Bottles of the Vapo-Cresolene chemicals are frequently found as well, sometimes empty but occasionally still with some of their original contents, which should be treated as a toxic material. These devices are often collected by miniature or night lamp collectors, or those with a pharmaceutical or medical interest. As found on Vapo-Cresolene box: Reg. U.S. Pat. Off. Registered, France, May 1st, 1887. Registered, Germany, 1899. Registered, England, May 15th, 1888. Registered, England, Feb. 3rd, 1897. Registered, Canada, April 12th, 1887.The Vapo-Cresolene Company was established in 1879. They maintained offices in New York City, first at 180 Fulton Street and then at 62 Cortlandt Street, and in the Leeming-Miles Building, 1651 Notre Dame Street, Montreal, Canada. As early as 1881, Messrs. Allen and Hanburys, Plough Court, London, were listed in a British pharmaceutical journal selling Page's Patent Vaporisers, as they must have been referred to prior to the trade name Vapo-Cresolene. In later advertisements, they are listed as Allen & Hanburys, Ltd., Sole Agents located at 27 Lombard Street, London. The company's production facility was located in Chatham, New Jersey. The Vapo-Cresolene Company survived well into the 1950's (as many 50's-era advertisements exist) and perhaps later and used a small electric unit as the heat source. In her book, Evolution of the Night Lamp, Ann Gilbert McDonald depicts another version of a vaporizing lamp with a twisted wire frame but does not attribute it to the Vapo-Cresolene company. It does, however, conform to Fig. 1 of the drawings in Carpenter's 1881 patent as seen below. The other lamp, Fig. 2, is a version more closely resembling the early advertisements seen in Britain, which are noticeably different than the models commonly available today.

The founts of the lamps are most often found in clear or colorless glass. The author has seen two examples of a light aqua color over the years. The burners are of the "Olmstead" type, some marked with V.C. CO. and five stars. There are two common versions of the burner - the one with rounded prongs (seen in left-hand margin) and the "spear-point" variety as seen in the patent drawing. The chimneys are more often the little milk glass versions seen in the lamp at the top of the page, but the clear upright version in the left-hand margin is fairly common and is believed to be an original item. The diminutive Vapo-Cresolene lamps were designed to burn kerosene and most of the founts are embossed as such. In his book entitled Chatham at the Crossing of the Fishawack John T. Cunningham wrote: "James H. Valentine made a crude vaporizer in 1879 in an effort to ease the pain of his young daughter, who lay racked with whooping cough. In desperation the father put a coal tar acid named Cresolene in a tin cup and suspended it over a small kerosene lamp. The girl found quick relief as soothing fumes filled the bedroom. Valentine recognized that he had discovered a commercial product: named Vapo for vaporizer and Cresolene for the coal tar acid." He writes further: "The first vaporizers were made in Kelley's Hall (over the grocery store), but Valentine did not have the capital to expand the market for his product beyond village limits. He was helped financially by George Shepard Page, and in time sold out to Page's four sons - Albion, Lawrence, Harry, and Raymond - and their sister Florence. The Pages shifted manufacturing to the old Stanley Hall near the Fairmount Cemetery." The Vapo-cresolene lamp was first patented by Elias H. Carpenter as a "Method Of And Apparatus For Volatilizing Cresylic Acid." Carpenter received his patent number 247,480 on September 27, 1881 and assigned same to James H. Valentine, who in turn assigned one-half to George Shepard Page. G.S. Page's son, Albion Lambert Page, would be president of the Vapo-Cresolene Company in the late 1880's. George Shepard Page (b. July 29, 1839, d. March 26, 1892) grew up in the coal tar business, having learned same from his father, Samuel Page, who distilled paraffin oils, varnishes, and other products in Boston, Mass. The 1862 Boston Directory lists them as Samuel Page & Son, doing business at 88 & 90 Water Street, and residing in Chelsea. One of George's first ventures in the early 1860's was the formation of the New York Coal Tar Chemical Company. George S. Page was recognized as one of the leaders in the coal tar and gas production fields both in the United States and Europe, where he frequently traveled. He developed and perfected many processes for the use of the by-products of these related industries, turning what was once considered waste products into something valuable (Slater 163-65). Since the cresolene "is a product of coal-tar possessing far greater power than carbolic acid in destroying germs of disease," (Adams 627) it was natural for him to take advantage of the disinfecting properties thereof, and develop a broad market for this product, both domestically and abroad.

From Carpenter's patent specification: "If a room is to be disinfected, one or more of the devices are supplied with cresylic acid, the lamps lighted, and the room is closed. The vapor will commence to rise from the basin soon after the lamp is lighted, for the liquid cresylic acid will vaporize at a low temperature; but the amount of vapor expelled will increase as the temperature is raised, and the vapor will fill every part of a room, enter every crevice, and pass through or between every article."On August 4, 1885, James Henry Valentine obtained Letters Patent No. 323,547 for a "Vaporizer." Depicted in the patent drawings are the familiar Vapo-Cresolene lamps, and a version designed to be used with a gas lamp. One of his main improvements over the previous version was a way to deflect the heated air away from the basin to prevent it from overheating by adding vent holes around the ring that holds the dish or basin. Many of these "lamps" are embossed around the ring with the August 4, 1885 and an August 8, 1888 patent date.

James H. Valentine also obtained two patents for the bottles used for the Vapo-Cresolene. These came in both two- and four-ounce sizes. Bottles conforming to the 1894 design patent were embossed with the U.S. and English patent dates: PATD US JUL 17, 94 ENG JUL 23, 94. Later, the bottles carried the 1895 patent date: PATD. US. JUNE 18-95 ENG. JULY 23-94 (Griffenhagen 95). The design of the bottles featured rows of pyramid-shaped hobnails on two sides of the bottle to indicate that the contents were poisonous, a common practice of the period. The other two faces of the bottles were smooth to facilitate the application of labels, which would not have been possible had the entire surface been covered with the hobs. Today, bottles can commonly be found in clear or colorless glass and different shades of aqua; and occasionally in dark amber or cobalt blue, another practice of the mid-1800's to indicate that the contents of the bottle were poisonous. Here's a short article from The Lowell Sun, (Lowell, Massachusetts) dated Thursday, December 12, 1912, reporting the death of a three year old boy who drank Vapo-Cresolene. Patents of James H. Valentine: 247,480 Sep 27, 1881 Volatilizer * 323,547 Aug 4, 1885 Vaporizer 374,720 Dec 13, 1887 Vaporizer D23,466 Jul 17, 1894 Bottle 541,133 Jun 18, 1895 Bottle 571,811 Nov 24, 1896 Volatilizer D30,880 May 30, 1899 Vaporizing vessel 651,150 Jun 5, 1900 Vaporizer 729,019 May 26, 1903 Vaporizer * assigned to Valentine by Carpenter Another less common form of medicinal lamp is Schering's Formalin Lamp. Early ads claimed: "Annihilates germs, removes odors, prevents disease, hastens convalescence..." This lamp was produced by the company of Schering & Glatz in New York City, with offices at 58 Maiden Lane.

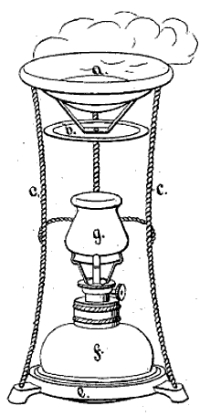

The Schering Formalin Lamp conforms to patent number 630,782 titled "Disinfecting By Means Of Formaldehyde." The patent was granted on August 8, 1899 to Albrecht Schmidt of Berlin, Germany and assigned to Chemische Fabrik auf Actien, vormals [meaning formerly] E. Schering, also of Germany. This lamp was designed to use Schering's Formalin Pastils, "which are entirely innocuous, [thus] the danger of employing the caustic liquid formalin is avoided" (circa 1902 advertisement). "The pastils are paraform, probably mixed with trioxymethylene. The apparatus is very simple, consisting essentially of a cup supported over an alcohol lamp. The pastils are placed in the cup and the heat of the alcohol flame causes them to disappear by conversion into formaldehyde" (Gatewood 635). On the same date as the Schmidt patent, Harry De Bacon Page, of Chatam, New Jersey, received a patent, number 630,401 for an "Vaporizer" which was an improvement to Valentine's patent no. 323,547. Harry was the older brother of Albion L., the son of George Shepard Page, and in 1903 was listed as the company treasurer. The author was curious about Harry's middle name, De Bacon, which turned out to be his mother's maiden name.

The following is excerpted from The Woman's Medical Journal detailing the procedures for using the lamp: "For the destruction of the less resistant disease organisms, such as the bacilli of diphtheria, typhoid fever and tuberculosis, forty 1-gramme (15.4 grains) pastils, the contents of two of the small boxes, will suffice in a medium-sized room, 3 m. (10 feet) high, 3 m. (10 feet) broad, and 8 m. (26 feet) long. Then the reservoir of the lamp is about half filled with alcohol after unscrewing the burner; the wick is lighted, and so regulated that it projects about 2-3 mm. (1/2 to 1/8 inch) above the tube. If wood alcohol is used as a fuel the wick should be about even with the tube (burner), as a too large flame will produce more heat than is required. More than 2 ounces wood alcohol should not be placed in the reservoir, which holds 4 ounces. The chimney, with the filled container, is then replaced upon the lamp" (p. 325). Therefore, unlike the Vapo-Cresolene lamp which was designed for kerosene, the Schering lamp was designed as an alcohol-fueled apparatus. The formalin lamps are much less common than the Vapo-Cresolene lamps. When found, they are often incomplete and finding the missing parts is nigh to impossible. Author's note: I purchased the fount and burner to a formalin lamp twenty-some years ago, as a naive collector, not knowing exactly what it was. At the time, I was collecting miniature or night lamps. Two decades later the top cup was given to me by another collector. The lamp is still without glass. The example from the eBay auction above is the only truly complete example that I have seen. I hold no hope of ever completing my example, but if some reader is in need of these parts, by all means please contact me. The thumbwheel on my example is unmarked; others seen have been embossed with the patent number - US PATENT 630,782.  Patent Search Interface Patent Search InterfaceTo view any of the patents referenced in this article, enter the patent number in the field below and click Query USPTO Database. This will open in a new window and take you to the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office Database - directly to the patent in question. Learn more about the USPTO here.

|