If you dig deep enough, there are lots of fragments of information available on Joshua Jenkins and the Suffolk Glass Works. There has been little of substance written and certainly nothing comprehensive. The author will attempt to assemble these "shards" into a reasonable timeline of the man and his glass company.

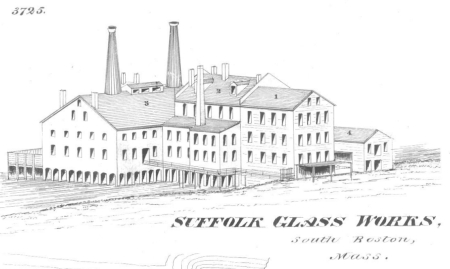

Davis April 10, 1806 Nancy October 25, 1807 Ruth December 5, 1809 Henriatte March 8, 1811 (twins) Henry March 11, 1811 (twins) Joshua September 17, 1813 Isaac August 4, 1816From the limited information available, the author believes that the Suffolk Glass Works was started sometime in the mid- to late-1840's. Dorothy Daniel lists the company as having started in 1845. While the specific sources of her information are not noted, they are listed as "Crockery and glass journals" and "Directories of the glass industry." (Daniel 396) There is an engraving of the factory building, believed to be circa 1849, that appeared in Gleason's Pictorial and Drawing Room Companion (Sammarco 11) an illustrated weekly newspaper that was popular during the period of the 1850's. From the picture, an observer would likely assume that it was a substantial manufacturing concern and in a prime location being located on the harbor and convenient to shipping. To date, the author has found no information on the glassworks during these early years. Author's note: thanks to a tip from Larry DeCan about an eBay auction, it has been verified that the Gleason's engraving is NOT of the Suffolk Glass Works as the caption reads, "View of the American Flint Glass Works, South Boston, From the Harbor" and is from an 1853 issue. I had been skeptical because the engraving is not consistent with any of the map images of the period showing second street where the glass works was located; my suspicion has been confirmed.

As early as 1835, Joshua Jenkins, then 22 years of age, shows up in the Boston Directory as a "painter and glazier." This listing remains consistent, with the exception of a few address changes, until 1859. A fairly consistent timeline can be stitched together by browsing through the Boston City Directories and Almanacs. On March 27, 1836, Joshua Jenkins married Lucy Jane Cole. The ceremony was held at the Phillips Church located at the intersection of A Street and Broadway in South Boston. The service was performed by Rev. Joy Hamlet Fairchild. Lucy Cole was born on May 30, 1815 in Weymouth, Mass., a town located about midway between Boston and Scituate. By the time of the 1850 census, Jenkins and his wife had five children: Amanda M., Charles H., Laura J., Emma L., and Flora D. Jenkins. In the 1850 census, Joshua Jenkins is listed as a "painter," having real estate assets in the amount of $50,000.00 - a tidy sum in those days - large land holdings or a glass manufactory, perhaps? Throughout the 1850's he is still listed as a painter. By 1860, the value of his real estate holdings had grown to $75,000.00 (an even tidier sum) and they had added three more children to their "brood:" James D., Maria A., and Clarence A. Jenkins. There was a clear pattern of having a child about every three years. His occupation in the 1860 census is listed as "glass manufacture."

Joshua Jenkins appears to have been a rather influential and civic-minded individual. In 1852 Jenkins was listed among the thirty largest taxpayers in South Boston (Toomey 183). Author's note: It would interesting to determine how "taxes" during the period were based. This could not have been, in my opinion, solely the result of his paint store or derivative income, but more likely on real property. Later in the article the real estate holdings of Jenkins will be explored, and I will research further into the tax structure of the period. It appears that Jenkins was in South Boston early enough to "snap up" a fair amount of property and would ultimately have a few rental houses, although many of his lots were vacant. Jenkins was very active in the South Boston political scene and his name appears in many newspaper clippings from the mid-1840's through the late-1860's in this context. Jenkins was a Democrat. In 1845 he was a member of the Board of Assessors serving as an assistant assessor for Ward 12. In the latter 1840's he began serving on the Common Council representing Ward 12. In 1852 he was on a committee to enforce the newly enacted liquor laws. In 1853 he was nominated as an Overseer for the House of Correction, but lost the election to another individual. Over the years, Jenkins sponsored many petitions for improvements around South Boston which included street paving, expansion of the municipal sewer system, and expanded street lighting on city streets. In May of 1855, after several failed attempts by others, Jenkins was instrumental in getting Washington Village and its 1300 inhabitants "...annexed to South Boston, thereby greatly increasing the extent of the territory of the Ward." (Simonds 227, Roberts 211)

An 1852 Map of the City of Boston and Immediate Neighborhood by H. McIntyre shows how undeveloped the area of Washington Village was at the time. Aside from the Dorchester Turnpike and Boston Street, there are only a handful of smaller streets noted. It was noted in A Record of the Streets, Alleys, Places, Etc. in the City of Boston that Lewis Street would be renamed Jenkins Street on August 7, 1855 (p. 261). Joshua Jenkins would eventually own most of the land along Jenkins Street all the way to Dorchester Bay, where the latter Suffolk Glass works would eventually be constructed, only to burn to the ground in 1871, and be rebuilt again. Even though the aforementioned book was published in 1910, Jenkins had a hand in compiling the information used therein before his death: "Mr. J. H. Jenkins, Mr. John W. Morrison and Mr. Irwin C. Cromack were employed by the Board to work in collaboration in the preparation of a list of the ways of the city, to be published without delay. These gentlemen, with long terms of service with the city in departments intimately connected with the laying out of its streets, were possessed of a special knowledge regarding them and were eminently fitted and qualified to carry this important undertaking to a successful and satisfactory completion." (A Record of the Streets. p. xiii).

In The History of South Boston, Toomey writes: "Of engine companies there were two, Mazeppa No. 1, house on Broadway, between F and Dorchester Streets, next to the Hawes School; and Perkins No. 2, house on Broadway, between B and C Streets. Elijah H. Goodwin was foreman of Mazeppa and Joshua Jenkins foreman of Perkins." Jenkins had been recommended for the foreman's job in July of 1851. In December of 1852 he resigned from the fire department, but remained a staunch supporter of the department. In 1855 he advocated for an additional engine to be purchased for Ward 12. In 1856 he was appointed to the Fireman's Cemetery Association which was formed to raise money for the purchase of cemetery plots "for the use of the past, present and future members of the Boston Fire Department." (Boston Daily Atlas, December 15, 1856). "On the evening of March 23, 1853, a meeting of citizens of was held for the purpose of organizing a Shade Tree Society." Joshua Jenkins served as one of the Directors of the Society. The goal of the society was to raise money for, and to plant shade trees along the the streets "which will be of incalculable benefit to future generations." (Simonds 221). Nearly a thousand trees were planted in the few years of the society's existence (Toomey 183). Joshua Jenkins was apparently not afraid to challenge the establishment. The author found the following newspaper clipping to be both interesting and amusing:

As early as 1845, Joshua Jenkins was a member of the Pulaski Guards having attained the rank of 3rd Lieutenant (Boston Daily Atlas, December 25, 1845). The Pulaski Guards, of South Boston, were chartered in 1836. They were part of The First Division of the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia. Their first captain was Col. Josiah L.C. Amee. Subsequently they changed their name to the "Mechanic Greys," but resumed their old name in 1841 (Roberts 211). In 1856, he was listed as captain of the First Regiment of Infantry, Company C (1856 Boston Directory). In 1857 Thomas Simonds writes, "They are now in a prosperous condition, under Capt. Joshua Jenkins as commander." He is still listed in the 1858 Directory as captain. On April 17, 1860 it is reported in the Boston Daily Advertiser that Jenkins had requested and received a discharge. Surely as a result of the Civil War, by July 1863 he's back in the ranks as a 1st Lieutenant (Boston Daily Advertiser, July 30, 1863). On August 17, 1863 the Boston Daily Advertiser reports that "The 3d and 4th companies of the State Guard have been raised...and have been officered as follows:...1st Lieut. Joshua Jenkins of Boston..., " Jenkins serving with the 3d Co. It is not known if Jenkins saw active duty, but the author could not find Jenkins' name on any of the published lists of Civil War veterans from Massachusetts.

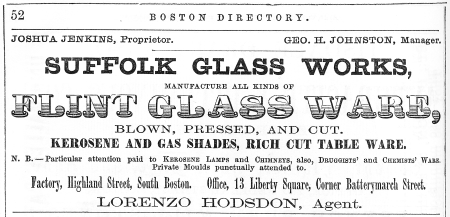

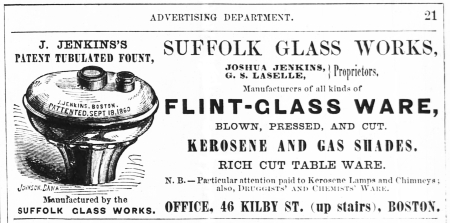

By the time of the 1860 census, Amanda, then twenty-three years of age had married. She and her husband, George H. Johnston, aged twenty-eight, resided at the Jenkins' family household at 4 Jenkins Street. They were married on February 18, 1859. George's occupation in the census that year is listed as Superintendent of the Suffolk Glass Works, and he is seen in the Suffolk Glass Works advertisement, circa 1859, below. In his article on Colonel George Henry Johnston, Bart Johnston wrote "George was born in 1832 and grew up in a glass making family whose factory was in rural South Boston, MA. He started the Suffolk Glass Works in 1855 and sold out to his father-in-law before the Civil War." The 1850 census confirms the part about growing up in a glassmaking family. George was the son of William and Susanna Caines Johnston. William was a glassmaker and was closely associated with Thomas Cains & Son and later the Phoenix Glass Works. The listing in the 1853 directory under glass manufactories reads: "Cains & Johnston, 35 Broad, and Second, near B, (Phoenix Works)." Thomas Cains was his maternal grandfather, so indeed, he descended from glassmaking lineage. The part about him starting the Suffolk Glass Company is a little more difficult to grasp as the author has uncovered little to substantiate it. This account of Johnston starting the glassworks was published in Wilcox's A Pioneer History of Becker County Minnesota in 1907. The verbal account was told to Mrs. Jessie C. West by Henry S. Jenkins, of Boston, on December 10, 1892. Henry S. Jenkins was the nephew of Joshua Jenkins; he was the son of Henry Jenkins (one of the twins), the older brother of Joshua. In 1892 he would have been about 55 years old. If the account is accurate, and not some distortion of the truth or "mis-remembering" of the facts, perhaps it was Johnston who bought the glassworks at the 1852 auction noted above. However, in the years preceding the Civil War, there is no apparent association with any glass business. In 1854-55 he is listed as a clerk at the post office, in 1856 as a policeman and in 1857 there is no occupation listed. In 1858 he is in business with his two younger brothers as Johnston & Bros. selling coal. In 1859 he is still listed as a partner with his brothers, and as manager of the Suffolk Glass Works, as noted in the 1859 advertisement shown below.

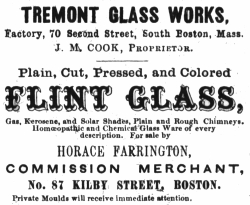

The author has located one additional reference to Johnston from the American Pottery & Glassware Reporter for November 6, 1884 as follows: "The Minneapolis Glass Company is organized with a capital of $75,000, and is under the management of George H. Johnston, a practical glass man of life-long experience, whose grandfather grafted the manufacture of flint glass on American industries in 1812. Mr. Johnston built and successfully managed both the Suffolk and Tremont glass works of Boston..." Thus it appears that Johnston went back to his glassmaking roots after he moved west and the notation clearly ties him back to the Suffolk Glass Works...if it is indeed accurate. In the end, this snippet raises more questions than it answers. Another question that begs to be answered is why Joshua Jenkins, a seemingly successful painter for a quarter of a century, suddenly enters into the manufacture of glassware? The timing of this association with his son-in-law George H. Johnston may hold the answer, but until further evidence and documentation is discovered, the question remains unanswered.

In May of 1861 George H. Johnston joined the 1st Massachusetts Infantry as a 1st Lieutenant. He was a courageous soldier and fought in many of the famous battles of the Civil War including Fredericksburg and Gettysburg and was ultimately promoted to Lt. Colonel and Adjutant General. After the war he returned to Boston. In 1871 he and Amanda traveled to Minnesota where, as a Trustee for the New England Colony, he founded the town of Detroit Lakes (Johnston 7).

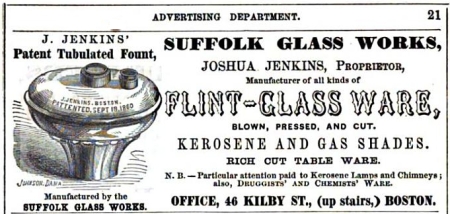

On September 18, 1860, Joshua Jenkins received Letters Patent No. 30,066 (a PDF file) for a "Mold for Glass Lamps." The patent depicts a mold for a pear-shaped bracket lamp fount. What Jenkins was claiming was a process for blowing the fount into a mold in such a manner that both the neck for the burner collar and a neck for a filler cap were formed, but the filler neck remained closed, like a bubble or dome. In the advertisements above, Jenkins calls this a "Tubulated Fount." To actually utilize the filler, one would have to cut or grind the top of the bubble off, thereby creating the opening for the collar and cap, or other stopper.

Two of the Jenkins' founts depicted in this article (the fount to the left and the images at the top of the page) are from the collection of Hugh Pribell. The pear-shaped fount likely precedes the patent as it is marked "PATENT APPLIED FOR" on the shoulder of the fount just above the ring. It retains its original fill cap which is embossed "PATENT APPLIED FOR J. JENKINS." The flatter bracket fount is embossed on the glass with the patent information: "J. JENKINS BOSTON MASS PATENTED SEPT. 18. 1860" just under where the bracket would hold the font. The fill cap is unmarked. Interestingly there is a circular grind mark on the shoulder of the lamp around the filler neck. It is believed that this is the result of the manufacturing process stated in the patent description whereby the dome of glass would be cut or ground away to make the opening for the fill cap. A very interesting find indeed! Thomas Gaffield, a Boston glass merchant and noted glass scholar of the period, interviewed Jenkins at the glassworks on May 6, 1862. The published report of the interview is particularly interesting because it gives some personal insight into Jenkins himself. Gaffield reported that Jenkins was meticulous about producing fine quality glassware. Jenkins spoke about how he took the needed steps to purify the materials he utilized in the manufacture of his flint glass. Particularly he spoke about purifying the manganese, which was used as a decolorant, by removing the alumina, iron and other impurities. Jenkins also produced his own cullet (broken scrap glass) through precisely controlled methods to ensure both quality and consistency. Gaffield noted that at the time of his visit "the iron molds in one tiny room of Jenkins' factory were worth $8,000, an indication of the expense of such molds." (Wilson) In his 1864 book, John Bishop states that "Boston is also the commercial centre of a number of very important Glass manufactories, whose works are in the immediate vicinity. The Boston and Sandwich Glass Company employ about 500 hands, and make about 60 tons of Cut and Pressed Glass per week. The New-England Glass Company has probably the most complete establishment in the United States for the manufacture of all kinds of Glassware. Their Opal Glass is said to be superior to a great portion of that produced in Europe. Besides these, there are the Suffolk Glass Works (Joshua Jenkins), the Mount Washington Glass Works (Timothy Howe, proprietor), the Phoenix Glass Company (J. B. Callender, agent), the Union Glassworks (Amory Houghton, agent), the Bay State Glass Co. (S. Slocomb, agent), and the long-established Glass Manufactory of Thomas Cain & Son, to which we have elsewhere alluded. The manufacture of Silvered Glass is extensively carried on by Alonzo E. Young, and from its showy and effective appearance is in great demand" (Bishop 669). Jenkins was in pretty good company! This interesting bit of information, circa 1863, was found relating to the employment women and children in the glass-making trades. "The Suffolk Glass Co. inform us they employ one girl in capping lamps, &c. The work affords plenty of air and exercise. Their girl is paid by the day, and earns $4 a week, working ten hours a day. The work done by women could not be given to men. The reason they employ a woman is that women are employed by others for the same work. Men could accomplish much more in their work, but not enough to pay the difference in their wages. Boys are sometimes employed for such work. Women receive $2 while learning. Spring and fall are the busy seasons, but work is furnished all the year. Board $2 to $2.50" (Penny 254). The author assumes that "capping lamps" refers to the application of, or cementing on, the brass collar to accept the burner or filler cap.

In the 1870 census, Joshua's occupation is once again listed as "painter." However, in the 1870 Boston Directory his professional entry is noted as treasurer of the Suffolk Glass Company. His son Charles H. Jenkins, then married with two children, was living next door, and lists his occupation as "Sup't Glass House." Charles' wife, Emily H. Jenkins, was a native of New Hampshire; his children, both boys, were named Charles D. and Harry H. Jenkins. Charles H. Jenkins will be listed as the Superintendent of the Suffolk Glass Works (or Company) for the years 1862 through 1884. From entries in the city directories for the years 1868 through 1876, Joshua is listed as the treasurer of the firm. On April 12, 1870, Charles H. Jenkins received Letters Patent No. 101,737 (a PDF file) for "Improvement In The Manufacture Of Glass." The patent is generally a formula or recipe for making white glass using waste marble. In the patent description he states: "The object of my invention is to utilize the waste chips of statuary marble, or other marble free from protocarbonate or other salts of iron, such as are prejudicial to the fabrication of good white glass." He goes on to state that the powdered marble reduces the manufacturing costs and will "utilize a substance of which vast quantities are or have heretofore been wasted." A true recycler! The Lowell Daily Citizen and News (Lowell, Mass.) reported on Saturday, March 25, 1871 that "The Suffolk Glass Works at Washington Village were completely destroyed by fire last night." Fortunately, there was adequate insurance coverage for the $30,000 loss that occurred. The factory was rebuilt after the fire, as seen below, and continued operation for many more years. A year and a half later, their offices located at 78 Water Street would be ravaged by the Great Boston Fire of 1872. This fire, which spanned the two-day period of November 9th and 10th, would ultimately destroy about 770 mostly commercial buildings covering approximately sixty-five acres in Boston. After the fire, the offices were relocated to 84 Washington Street.

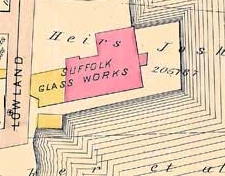

The late Kenneth Wilson noted that between the years of 1880 and 1885 the business was run by S.B. Lowland, an agent who had worked with Jenkins. The author challenges this assumption by proposing the following: Wilson misinterpreted the entries in the city directories at that time, or mistakenly accepted the research of others in the belief that the entry "Suffolk Glass Works, Lowland, S.B." was a person, when in actuality it is merely the address of the glassworks at the time. This can be substantiated by an 1884 map of South Boston which shows the Suffolk Glass Works - the location being Lowland street, and S.B. being the abbreviation for South Boston. The map indicates the property adjacent to the glassworks and that of "Heirs Joshua Jenkins," and also shows the substantial property still owned by Mrs. Lucy Jenkins. Additionally, the author found no entries in the directories of anyone with the surname Lowland.

The 1878 and 1879 Boston City Directories list his home address as North Scituate, so it is assumed that he was making preparations for his retirement from the glass business and gradually removing himself from the day-to-day operations of the company. The 1880 city directory entry states: "Jenkins Joshua, removed to Scituate." In the 1880 census enumeration conducted in June, he had clearly returned to his birthplace of Scituate, Massachusetts where he is listed as "Ret. Merchant." [Does it stand for retired or retail?] With him are his wife Lucy, three of their daughters, Laura, Maria and Emma L. White, and Emma's four year old daughter Helen W. White (1880 census).

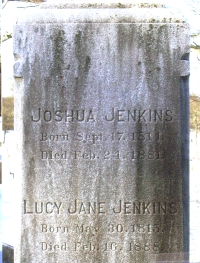

In 1869 the Baptist Chapel relocated into a new church that was erected in North Scituate. The old meetinghouse, which was originally constructed in 1826, was sold by the Society to Joshua Jenkins for $600.00 (Bonney). In 1870, Joshua Jenkins renovated the interior by removing the pulpit and pews thereby creating an open floor plan. He named the building Jenkins Hall. Jenkins Hall was akin to the community centers of today. "Jenkins provided the Scituate community with a host of entertainments which included dances, recitals and musicals. In addition, Jenkins also rented the hall out to various fraternal organizations that gained popularity in the late 19th century. Among those groups that used the hall was a group of local Civil War veterans. In 1875, these men formed Post 31 Grand Army of the Republic. In 1883, Post 31 G.A.R. purchased the hall from the estate of Joshua Jenkins. That same year with great ceremony the hall was renamed Grand Army Hall" (The Scituate Historical Society). Joshua Jenkins died in Scituate on February 21, 1881, aged 68 years and six months. The cause of his death was listed as diabetes; his occupation, as listed on his death certificate, was "farmer." The author would like to think that he retired to more leisurely pursuits and gardening, rather than farming. Farming is hard work and doesn't sound like much of a "retirement," but from the assessor's listing above, it would appear that he did indeed have a working farm. Joshua Jenkins, and later his wife Lucy, were buried in the Mt. Hope Cemetery in Boston. The monument marking the grave site is shown below.

By 1884, the company had fallen on hard times. A notice in the American Pottery & Glassware Reporter for July 3, 1884 stated: "The Suffolk Glass Co., of Boston, Mass., are in insolvency. A meeting of the creditors was held on June 27 to choose assignees. The liabilities are not stated. The Suffolk Glass Works consist of two 7-pot furnaces. They made tableware, lamps and chimneys. C.H. Jenkins and Lorenzo Hodsdon were partners in the concern." On December 12, 1884 the Suffolk Glass Company was reincorporated with a capital stock of $50,000, and took the plant of the late Suffolk Glass Works (A. P. & G. Reporter, May 7, 1885). Apparently this attempt at reorganization ultimately proved futile as early in 1885 small legal notices run in many newspapers proclaimed the bad news: "Soon Got Enough. The Suffolk Glass company, of Boston, has failed. It was incorporated in December last, with a capital stock of $50,000 to manufacture prismatic lenses and illuminating window glass." (The Logansport [Indiana] Daily Pharos, April 30, 1885). A legal notice in re William Hodsdon vs. Charles H. Jenkins appeared in the Boston Daily Advertiser on, Tuesday, June 30, 1885. The issue was over a promissory note to L. Hodsdon and states that he is a "...member of the firm of Charles H. Jenkins & Co's. the maker of the note. The author assumes this is Lorenzo Hodsdon, former long-term employee and agent for the Suffolk Glass Works. There is no information readily available on Charles H. Jenkins & Company.

The following appears in the September 17, 1885 edition of the Pottery & Glassware Reporter: "The Suffolk Glass Co. has been reorganized into the Boston Antique Glass Co., which is now erecting at South Boston a new building to make colored window glass." There is little information on this incarnation of the company. They appear in the Boston Directories until at least 1892 under the headings of "Stained and Cut Glass" or "Glass Stainers" and most often at "53 Devonshire, rm. 6." The address of the factory is once given as Lowland Street, but based upon the article, it appears that they built a new factory rather than occupied the old one. Additionally, a supplement attached to the Barlow Insurance Survey noted above reads: "SUFFOLK GLASS WORKS, SOUTH BOSTON, MASS. Idle. All locked up and property for sale. December 1886." An article in Boston Daily Advertiser on Friday, April 13, 1888 states: "For Sale or To Let. The property formerly known as the Suffolk Glass Works, on Lowland street, South Boston, and the land connected with the same, consisting of about 230,000 square feet. The buildings are in excellent repair, and have five new fire brick furnaces suitable for smelting, etc. in the same. Will sell on easy terms or will let low." An 1891 map of South Boston published by G. W. Bromley & Co., shows the former Suffolk Glass Works building is with a new occupant - The Oakman Manufacturing Company. The company is shown to occupy the wooden portion of the building bordering Lowland Street, which by then had been renamed Mercer Street. [Renaming was effective March 1, 1888.] The Oakman Mfg. Co. was in operation between 1890 and 1897. Their office was at 219 State Street. During its seven year existence, Samuel Oakman was noted as treasurer of the company. In 1892 the company changed to the Oakman Glass Works. Oakman made glass insulators and "specialized in larger, heavy power distribution designs, especially those intended for supporting heavy direct-current trolley car cables." (Maurath). In 1900, the former Suffolk Glass Works building, which had sat vacant for a number of years, was destroyed by fire (Toomey 239). Charles H. Jenkins died on December 12, 1903. He was 63 years of age. The cause of death was noted as Diabetes Mellitus, from which he had suffered for three years. He was buried in the Mt. Hope Cemetery. The story of the Suffolk Glass Works had finally come to a close.

Author's note: I have spoken to both Hugh Pribell and Jamie T. Jones about the founts in their collections. Both gentlemen have examples of the pre-patent founts with the embossed filler caps and the patent-dated varieties. Both agree that the pre-patent founts are heavier in comparison, indicating somewhat thicker glass. Jamie also pointed out, and Hugh confirmed, that the patent-dated founts have a built-up shoulder around the filler neck area and the pre-patent versions do not. Clearly Jenkins made a change in the mold, but the reasoning is uncertain. It is possible that it was done to strengthen the filler neck area to reduce stresses from the cutting/grinding process, or to strengthen that area of the thinner-walled, lighter founts, or both. It could have also been an aesthetic change as the filler collar now has a level ledge upon which to sit, rather than on the curved shoulder of the earlier version. Should the reader have any additional observations regarding J. Jenkins founts in his or her collection, please contact me. I would also be interested in hearing about any other items - chimneys, lamps or other glass products, that are attributable to the Suffolk Glass Works.

|

| Reference Desk | Lamp Information | Other Resources | On-Line Shopping |

An On-Line Resource for Lighting Researchers and Collectors

of Oil and Kerosene Lamps, Burners and other Trimmings

Fill Cap marked "PATENT APPLIED FOR J. JENKINS" Note the radial scratches on the enlarged image that resulted from unscrewing the burner as it scraped across the top of the cap.

Fill Cap marked "PATENT APPLIED FOR J. JENKINS" Note the radial scratches on the enlarged image that resulted from unscrewing the burner as it scraped across the top of the cap.Enlarge image [+] |

Detail of grinding marks on the fount thought to be the result of the process for forming the filler neck as outlined in the patent description.

Detail of grinding marks on the fount thought to be the result of the process for forming the filler neck as outlined in the patent description.Enlarge image [+] |

Joshua Jenkins and The Suffolk Glass Works

The curious tale of a painter turned glassmaker turned farmer. ^ Top of Page

search terms for vapo cresolene, vapo cresoline, vapo-cresoline, shering, shering's

Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions of Use | Announcements

Copyright © 2001-2011 ~ Daniel Edminster | The Lampworks ~ All Rights Reserved